International Business Machines

Endicott, NY

International Business Machines (IBM) has a long and storied history in Upstate New York. The company was formed as International Time Recording Company (IRT) in 1911 and reorganized as IBM in 1924. IRT was lured from Binghamton to Endicott by representatives of the Endicott Johnson Shoe Company, a large but now defunct employer in the region. Endicott was the heart of IBM manufacturing, and everything from punch cards to mainframes were built within the sprawling factory campus.

Endicott is a member of the Triple Cities, which includes Binghamton and Johnson City to the West. What began as farmland was transformed over the years by IBM into a manufacturing and research hub that drove technological innovation.

Notable facilities included the IBM Country Club & Homestead, which was established as a retreat for all IBM employees, their families, and as an annual gathering place for members of the “One Hundred Percent Club”. What started as a modest 2 floor factory belonging to the Bundy Manufacturing Co. evolved into IBM Plant No. 1, which encompassed over 4 million sq. ft. of production floorspace. The 1933 laboratory pictured above still sports IBM’s motto, “THINK”, coined by Thomas J. Watson Sr. The IBM School, which sits dormant across from the factories on North Street, was a learning destination for salespersons aiming to better understand the technologies they sold.

I set out to document the legacy of IBM in Endicott over the winter months of 2021, making many trips to shoot the 5x rolls of 35mm and multiple sheets of 4x5 film you see here.

A Dormant Industral Legacy

Plant No. 1 | Endicott Factory campus

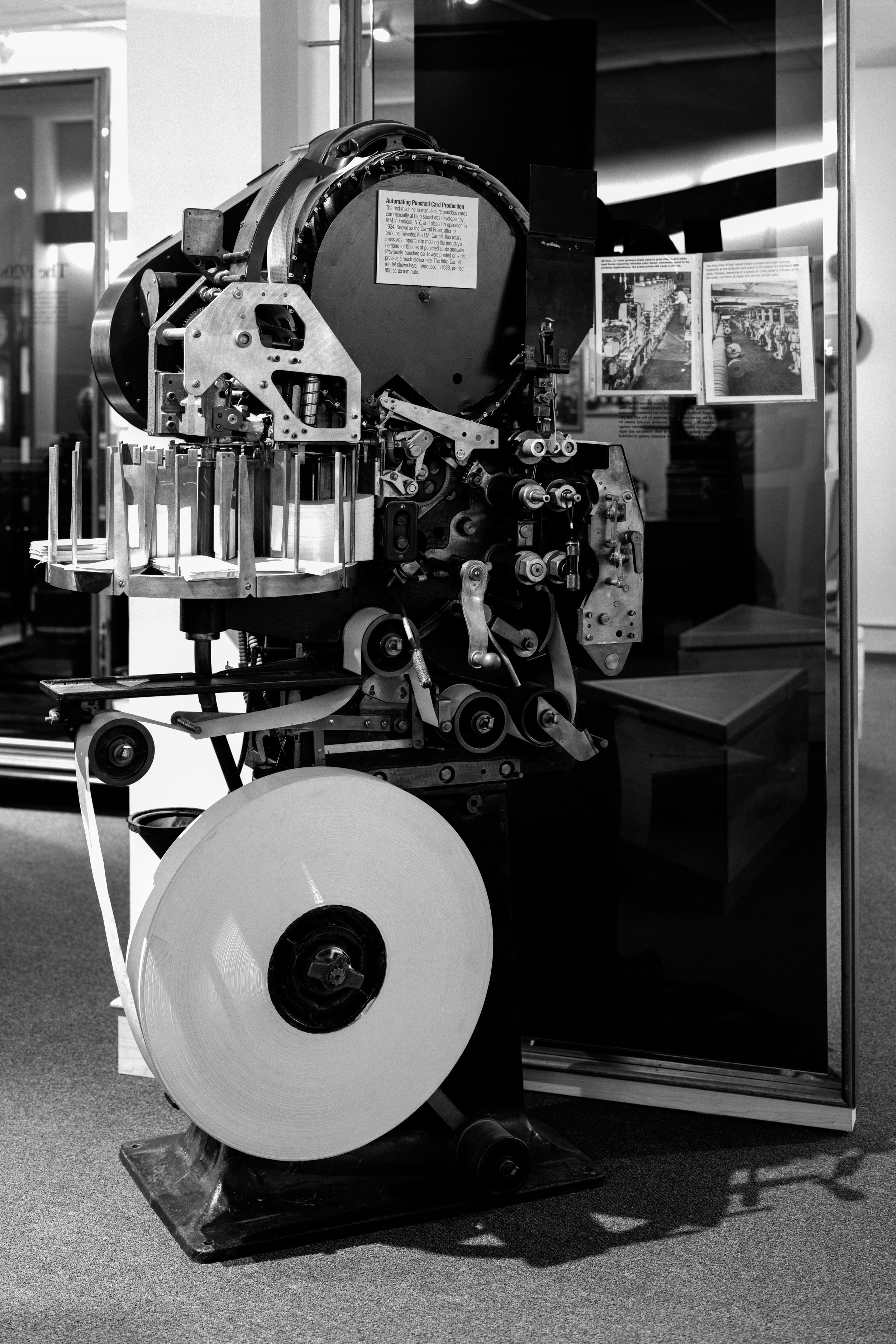

The most prominent feature of IBM’s industrial legacy in Endicott is the Huron Campus, which sold in 2021 to Phoenix Investors. The campus is a collection of factories and office buildings that one supported the sprawling operations of IBM manufacturing and research. IBM pulled out of Endicott in the late 90s, leaving behind less than 1,000 employees in a handful of leased building by 2002. For comparison, 17,000 employees worked for IBM in the Triple Cities at its peak. The first factory building, constructed by the Bundy Manufacturing Co. in 1907, was incorporated over time into the larger factory complex and can be seen from the bridge that carries N. McKinley Ave over the railroad tracks. A whole host of products from time clocks to scales, adding machines to typewriters, and punch cards in the millions rolled off the production lines that once hummed with activity.

The sheer scale of these dormant factories pose the greatest threat to their survival. Kodak, for example, spends millions of dollars every year to heat its dormant Hawkeye factory building in Rochester. The drastic temperature changes that accompany New York’s winters can wreak havoc on unoccupied structures. Exterior paint takes a beating and beings to peal, which allows water to seep into the concrete. This water expands when freezing temperatures hit, causing cracks to form.

Impact from years of deferred maintenance can be seen above the IBM factory’s front doors where frescos depicting an hour glass, abacus, and scale have been decimated by the elements. These frescos tie back to the technologies that built the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company’s (CTR) core lines of business - time clocks, adding machines, and scales.

When millions of men enlisted in WWII, IBM employees left the factory floors to fill the ranks of the nation’s military. IBM was called upon to provide computing equipment to the US government, which was attempting to organize a steady stream of draftees. IBM’s first government contract was won in 1935, when they were tasked with providing electromechanical processing equipment for the world’s biggest accounting job: the newly enacted Social Security program. While other companies laid off workers during the depression, IBM continued to build machines and amassed a stockpile of them at Endicott. This stockpile of IBM Type 77 machines was ready and waiting to fulfill the Social Security Administration program’s order, which won them the lucrative government contract.

By war’s end, 57 of IBM Endicott’s 30,000 employees would be killed in WWII. Two monuments were erected in their honor by the employees of IBM Endicott: one, a flagpole with metal eagles, wings stretched skyward, still flies the American flag next to the former IBM research building on North Street. The other, a white marble pillar dedicated in 1947, was moved to nearby Highland Park when the IBM Country Club closed. The Endicott factory earned an Army Navy E Award for exemplary output and attendance contributing to the war effort in 1942. On a personal note, my Grandmother earned one of those awards while working at the Hercules Powder Plant in Kenville, NJ. I still have the special card and pin she was given stashed away at home.

Glendale Development & Programming Laboratory

A 10 minute drive down the road from the former factory is the Glendale Development & Programming Laboratory. Occupied by the likes of New York State and Lockheed Martin today, the complex stands as a reminder of the groundbreaking research conducted at IBM. Comprised of 121 acres and 17 buildings, the complex was mostly focused on software development and printers. The lab’s mission was to develop mid-range computer systems, software, applications, and packaged solutions marketed to other businesses.

Life in The IBM Valley

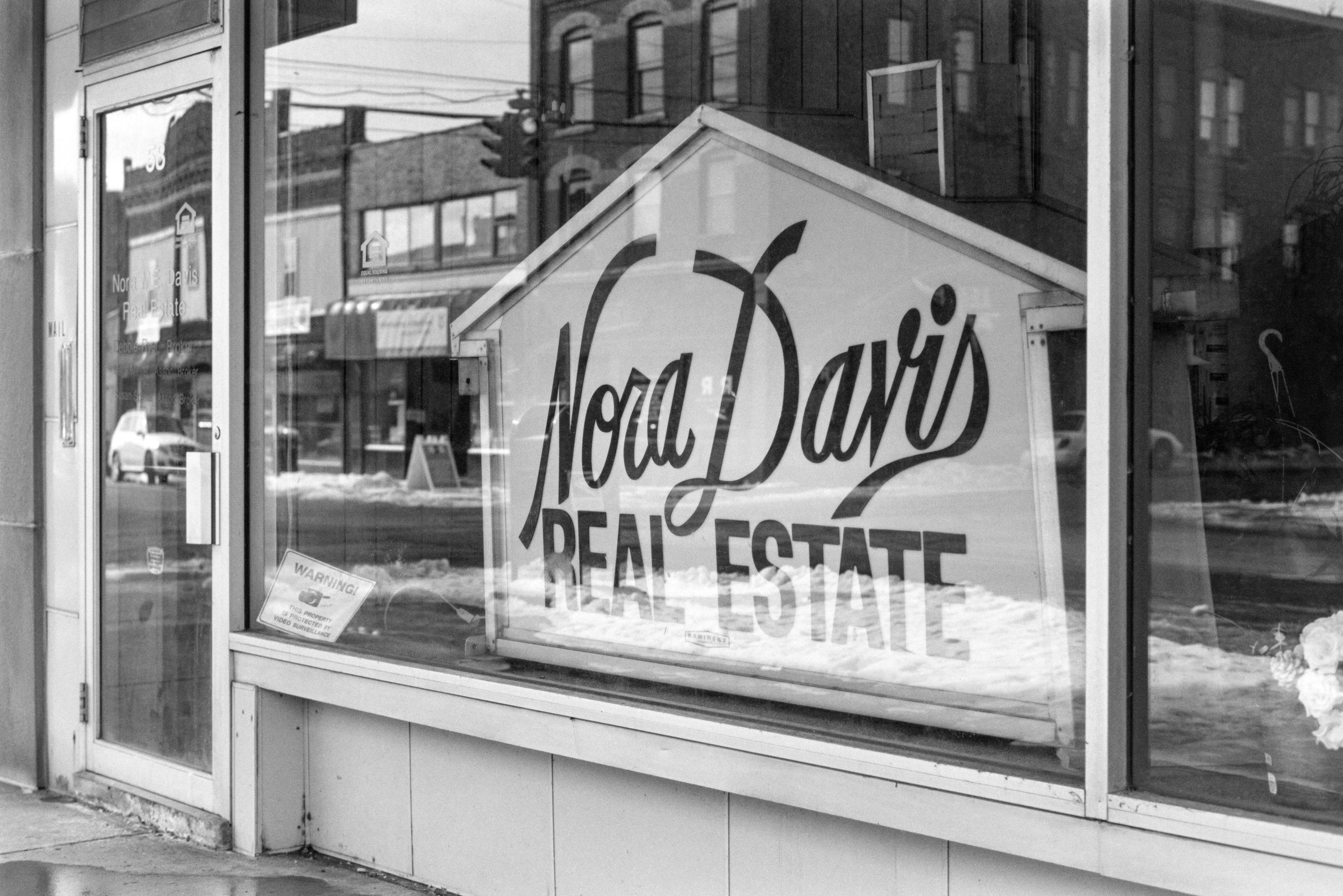

Many of the buildings around Endicott seem frozen in time, a reminder of peak IBM in the 1960s and 70s when the company had just introduced the System/360. Modernist architecture dominates the municipal buildings of Endicott: Town Hall, the George F. Johnson Library, and the Police Station were all completed in the mid-60s. The library itself generated some controversy as it’s construction involved the demolition of a local legend’s home, George F. Johnson, who founded the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company. What was the “Ideal Home Library” was ultimately demolished to make way for the library we see today.

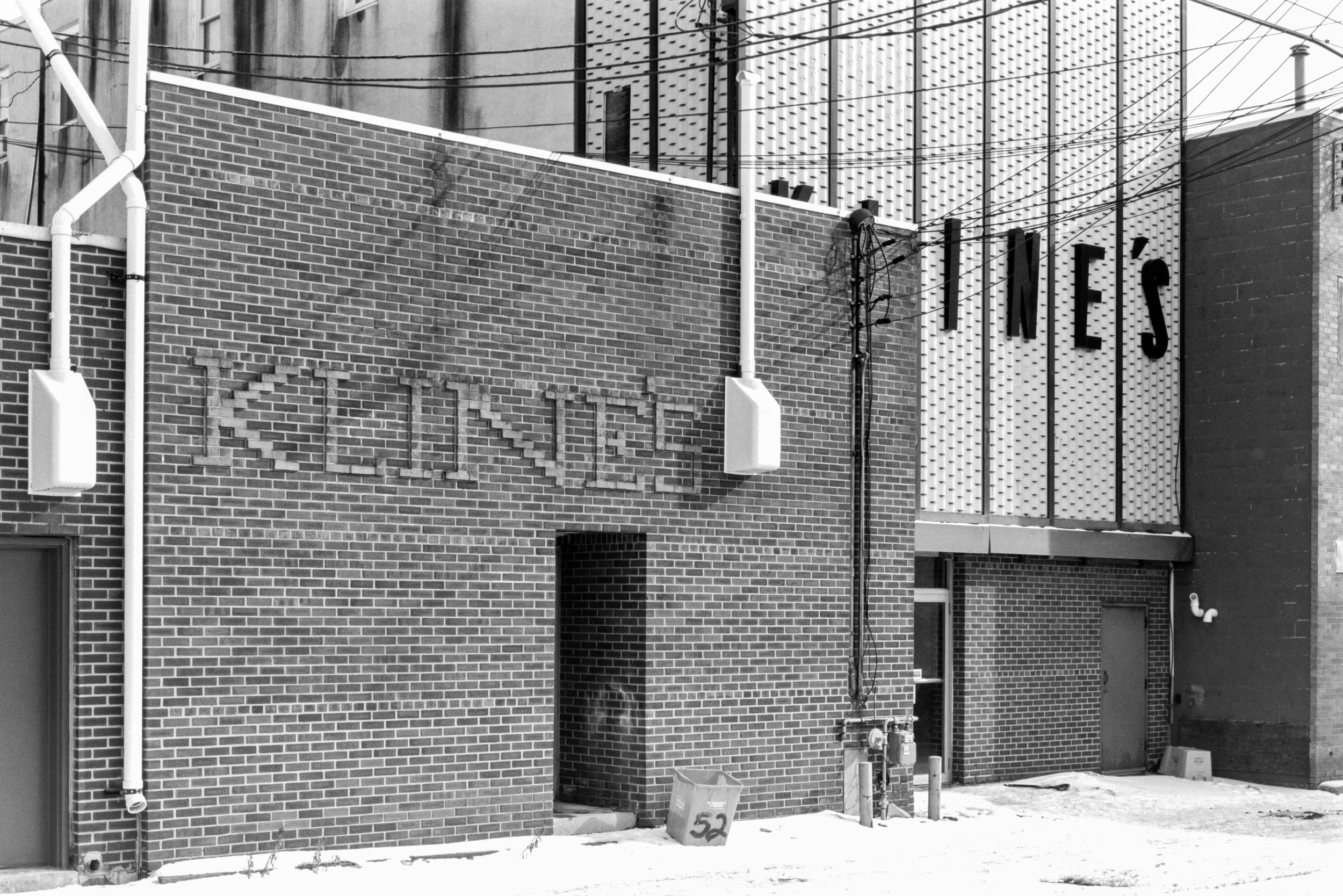

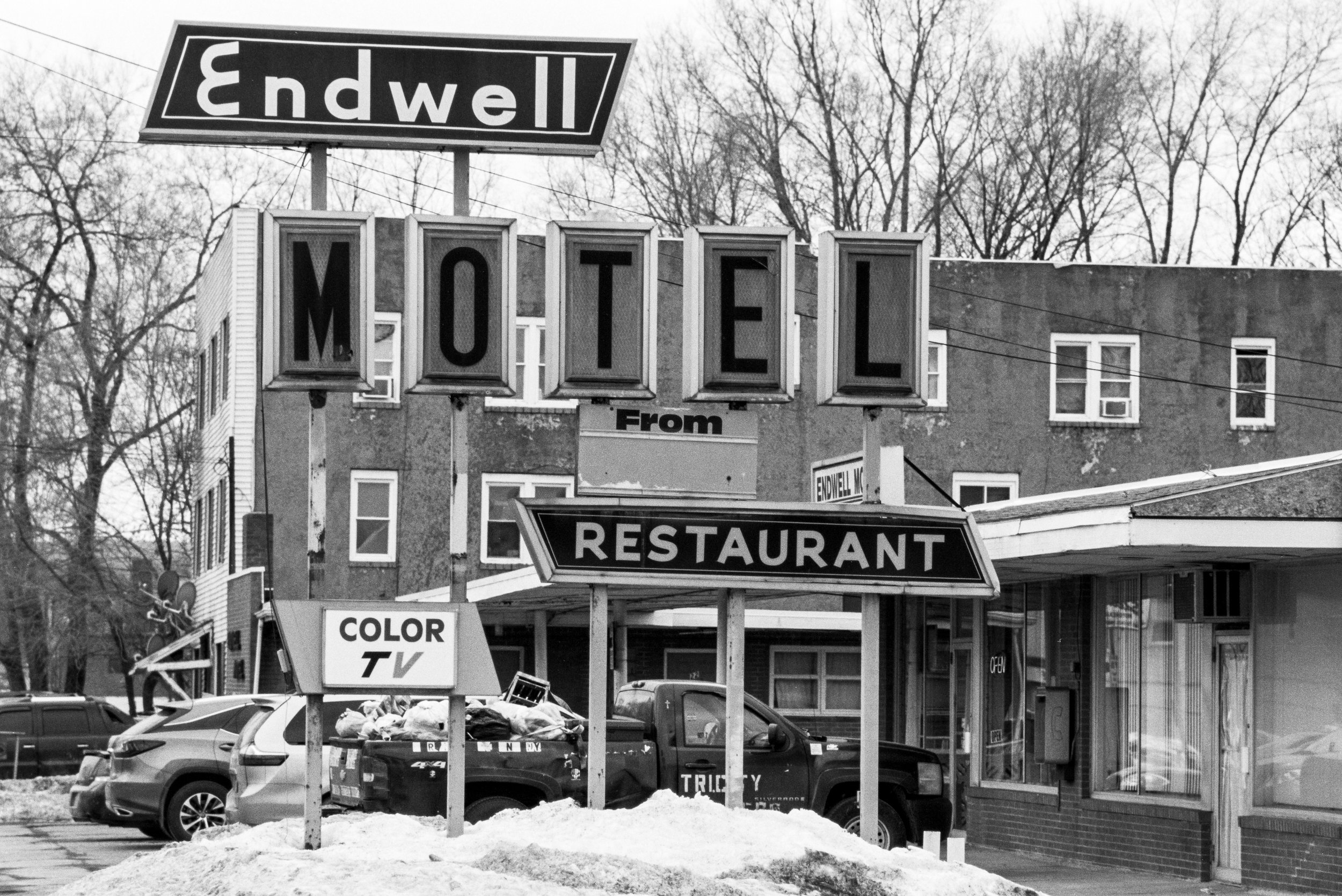

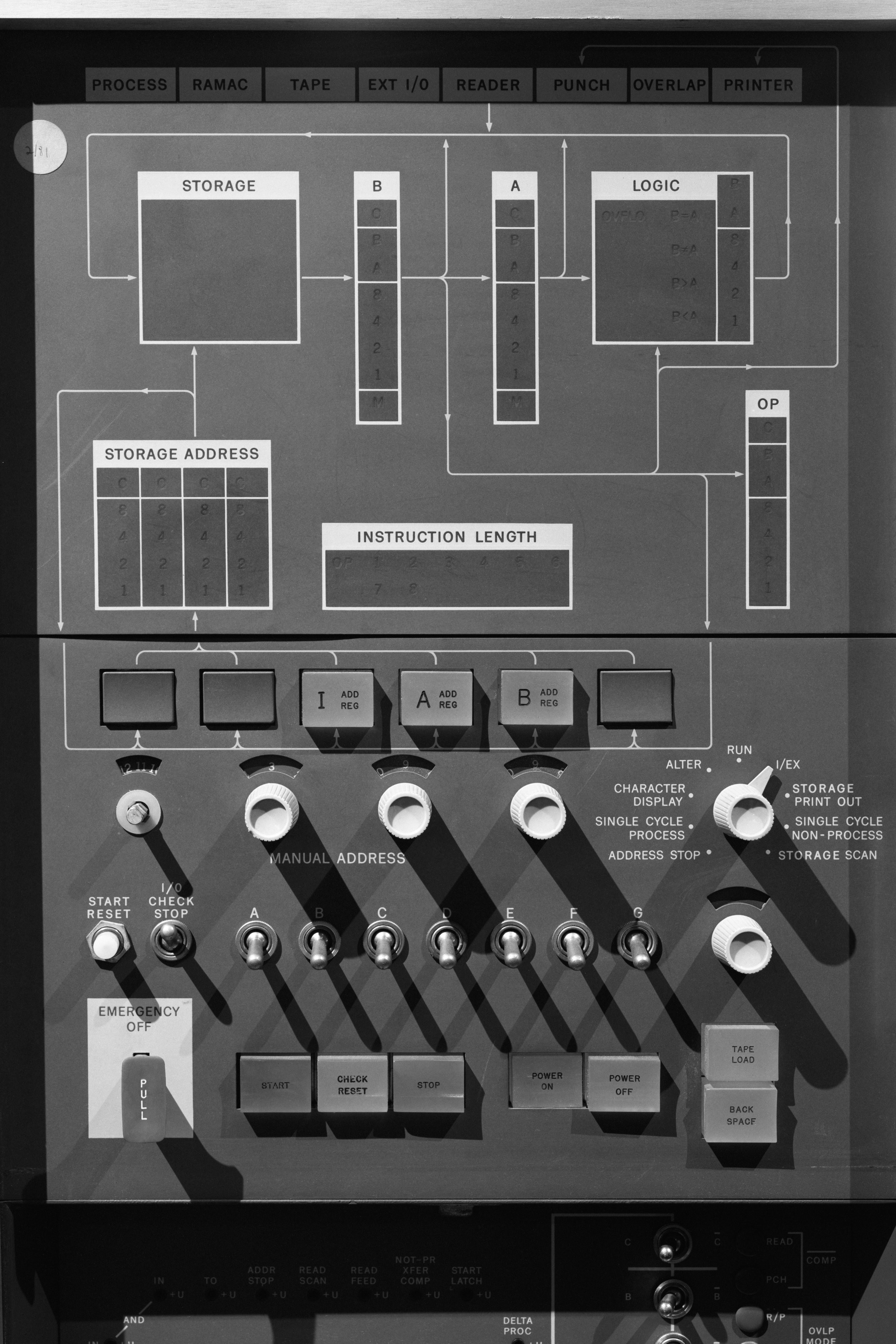

Stepping inside Town Hall is like being rocketed back to the height of the Cold War - yellow “Fallout Shelter” civil defense signs are plastered around the building and a beautiful mural in the atrium depicts the now defunct industries that built Endicott. The long gone Endicott-Johnson smoke stack, magnetic tape reels, and the iconic punch card are all prominently features of the mural. Other buildings around Endicott reflect Space Age design sensibilities - a shuttered department store on the corner of Washington Ave & Broad Street, Kline’s, and the Endwell Motel.

Endicott History & Heritage Center

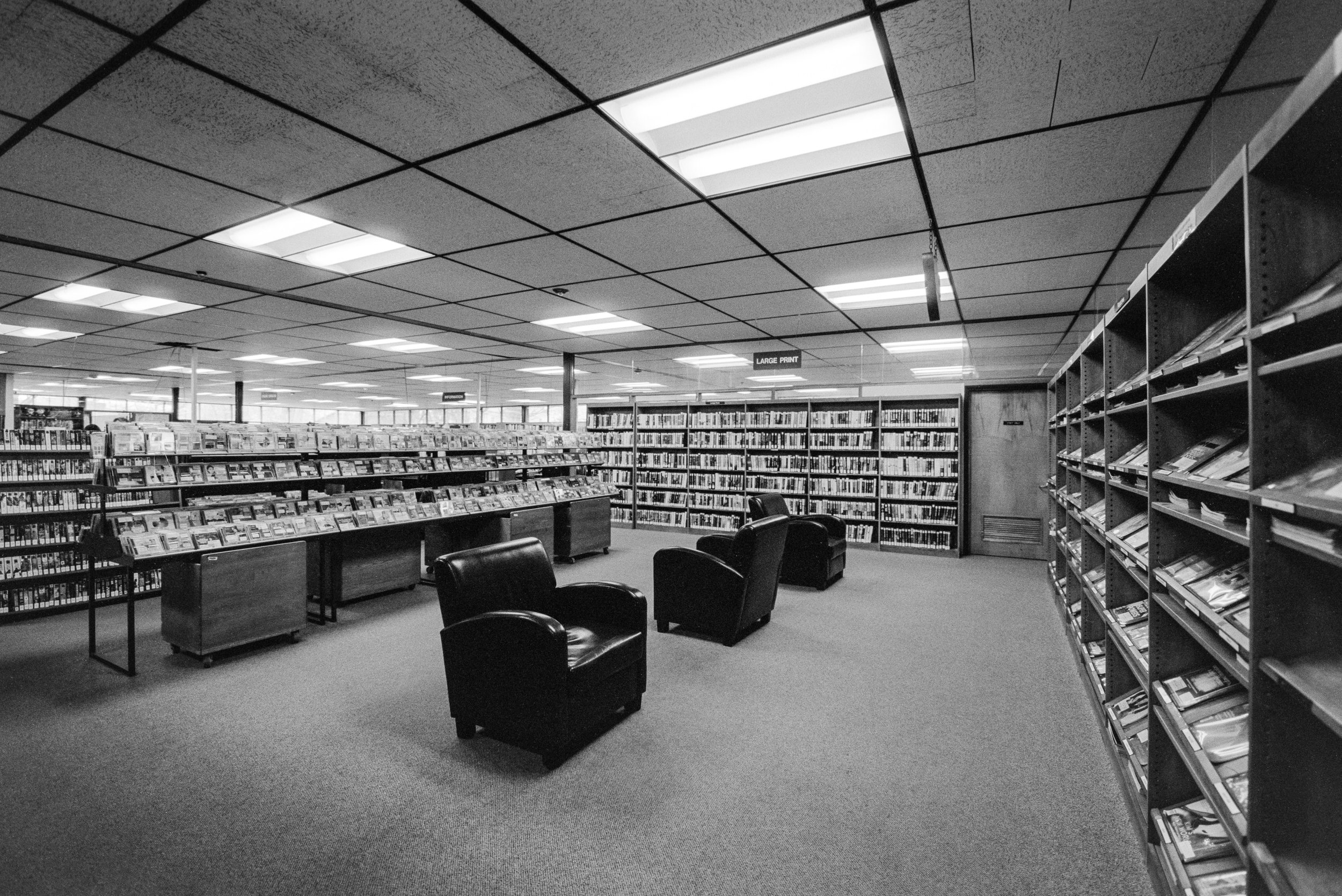

The Endicott History & Heritage Center, which occupies an old department store at 40 Washington Ave, houses a collection of computing equipment that details the history of IBM. The Old Village of Union Historical Society negotiated a long term lease of the displays when IBM pulled out of Endicott, and volunteers (many of whom are ex-IBM employees) offer guided tours on the weekends. It’s a great place to visit if you’re in town, and the museum collection includes examples of everything from the first mechanical time clocks to the the last IBM mainframes built at Endicott.

The IBM Country Club & Homestead

One thing that sets the IBM of days past apart from the prevalent corporate culture of today is the concept of employee loyalty, and the idea that dedicated employees create a better work product. In IBM’s heyday, it was generally accepted that if you were committed to your position you’d have a job for life. This statement seems to have held true - at the first meeting of the quarter-century club (employees with 25 years of service) in 1924, there were 42 employees in attendance. In 1946 there were 341, and in 1974 there were 8,400. IBM even planned housing communities to help employees “attain the dream of every man”, home ownership. While it might be common today to move between companies every 5 to 10 years, that certainly wasn’t the norm during Thomas J. Watson Sr.’s time.

Part of this commitment to employee loyalty was the IBM Country Club & Homestead. The Homestead functioned as a hotel and classroom for visitors to the Endicott area, and as a home for the “Tent City” that sprang up each year to house members of the “One Hundred Percent Club”. IBM salesmen from across the country who reached or exceeded 100% of their sales quota would convene at the Homestead once a year for a sort of sales conference. The first gathering held at the Homestead took place in the 1930s.

All employees, from the factory floor to board room, were members of the country club and could take advantage of its facilities. A golf course, swimming and wading pools, billiard hall, dance floor, bowling alley, and even a restaurant were all staples of the country club. A complete dinner of southern fried chicken, cranberry sauce, green beans, mashed potatoes, rolls, and choice of desert would set you back 35¢. No alcohol was ever served at an IBM event and the outfit of the day was a white button down shirt, tie, and dark suit no matter the weather. I can only imagine how difficult it was to keep that white shirt stain-free on the factory floor or while out on a service call.

Over the course of my many trips to Endicott and the research I conducted for this project, I began to wonder where the IBMs of the world went - those industrial behemoths, helmed by C-Suite executives like Thomas J. Watson Sr. or George F. Johnson who seemed to be concerned about their employees’ well being. The ex-IBM employees I’ve talked to in Endicott seem to echo the sentiment of good times with the company, developing systems familiar to me as an IT Auditor like RACF, TWS, CICS, and MVS. I thought it was neat to see where the IBM z/OS systems I audit every day at work got their start in the days of punch cards and tabulators. Endicott is a Space Age time capsule, a community built on the success of an employer who packed up shop when international competition decimated US manufacturing capacity.

This project is the first in a number of future explorations documenting the cities of Upstate New York and the companies that built them including Corning Inc, Kodak, Xerox, Bausch & Lomb, and General Electric, so stay tuned!