I’m a little late to the game with this review because I’ve been shooting Ferrania P30 since it was first available, and I figured it was about time I put my thoughts on paper for anybody else wondering whether it’s worth their time and money to try this film. It’s always exciting to see new (or revived) emulsions enter the market. P30 was resurrected by the team at FILM Ferrania in Italy, who launched a Kickstarter campaign to buy the rights to Ferrania’s emulsions after the company ceased operation in 2009. As of 2021, P30 is only available in 35mm with plans to produce 120 at some point in the future. Bringing back a defunct emulsion is no easy task, and there have been many delays over the years (much to the chagrin of Kickstarter backers). I purchased two rolls in late 2017, giving one to a friend and shooting the other one myself. The Bethlehem Steel series here on my website was actually shot on P30 in early 2019.

Introduction & Shooting

So, what do I think of Ferrania P30? It certainly won’t replace FP4 Plus or Across 100 in my arsenal, but P30 does have a place in my film fridge. It’s a film suited to very specific situations and subjects, and I wouldn’t suggest shooting it on anything but a clear, sunny day. You need to be very careful with this film and contrasty scenes – the emulsion does not leave much information in the shadows and it’s very easy to underexpose a scene. I tend to apply +.3 or +.7 exposure compensation on my F100 when the subject is primarily in the shadows. Trust your instincts and you’ll end up with a roll of rich, if contrasty, negatives.

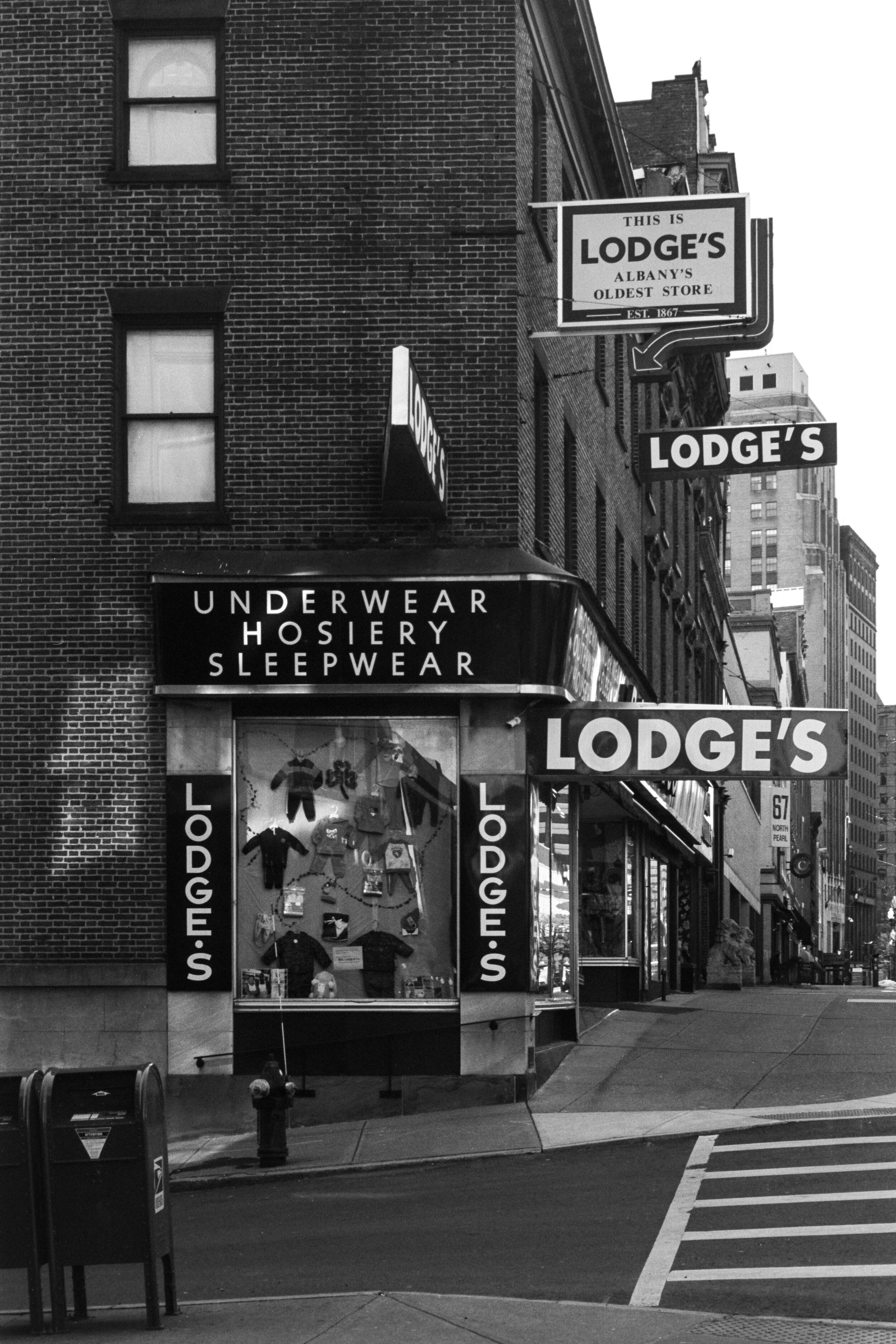

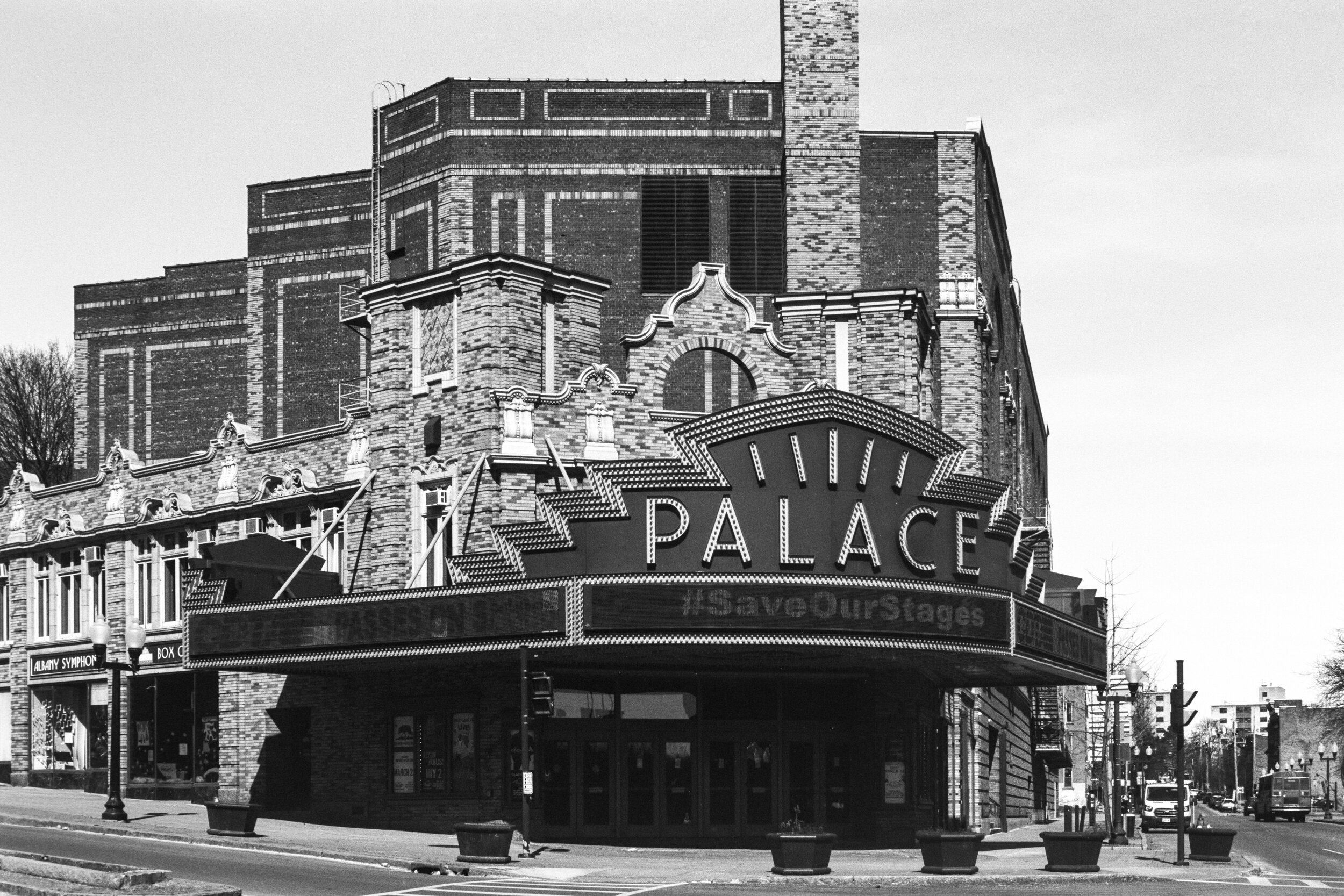

This film behaves unlike any other B&W film I regularly shoot. P30 stays true to its roots as a motion picture film stock. The high-contrast look might not be for everybody, but I’m a fan. The contrast renders industrial and architectural scenes, like Bethlehem Steel and the locations I recently shot in Albany, in a dramatic way that adds to the subject. Unfortunately, I can’t offer any advice on portraiture with P30 but I’d suggest spot metering over matrix metering. You need to be very careful to make sure the shadow detail of your subject isn’t lost.

Development

I’ve done quite a bit of experimentation with film/developer combos, and have had the best results with Rodinal 1:50 @ 14 minutes. Rodinal shines with slow speed films like P30. My tests with HC-110 and ILFOTEC DD-X, my go-to developer, didn’t produce the level of sharpness I was after. No matter what you do, P30 will leave you with a rather thin negative and little shadow detail. There were quite a few shots from Bethlehem Steel which I had to trash because the negatives were just too thin. I learned my lesson though, and the rolls I’ve shot since have had a much higher percentage of keepers. Although the negatives seem thin, they’re full of detail when you scan them. I can’t comment on how they perform when darkroom printing, but I get good results with my Epson V800 and even better results with my Nikon ES-2/D7200 combo.

Image Gallery

Final Thoughts

Ferrania P30 is not a film that will work for everybody in every situation, but it’s a great choice if you’re looking for dramatic, contrasty negatives. The supply of P30 has been sporadic at best, and the COVID-19 pandemic certainly hasn’t helped remedy the issue. While there were initial complaints about Ferrania’s quality control in the early batches of P30, I haven’t seen any issues with the latest batch of five rolls I purchased. This is the type of film that you’ll know the right project for it when you see it, and I’d highly recommend you pick up a roll and give it a try!