I’ve been toying with the idea of a more compact alternative to my D810 for about a year, and over the summer I found this used Sony RX100VA for a good price at B&H. Broadly, there are two categories of compact cameras available today for the prosumer market: full-frame fixed lens cameras and 1” compact cameras, the latter category including the RX100 series. There’s a lot to like about this little camera, but I’d describe my experience so far with the RX100VA as love-hate. A common saying in photography goes “the best camera is the one that’s with you”, which was one of the primary drivers behind picking this thing up. While I appreciate everything this camera can do, I think the #1 lesson I’ve learned is to temper my expectations - it’s not my D810 after all!

Lens & METERING

With a 24-70mm equivalent lens and a wide f/1.8-2.8 aperture, the camera encompasses focal lengths that I use most often. I specifically chose the VA variant because it’s the most recent model with the 24-70mm lens included - all models since the VA have a longer 24-200mm f/2.8-4.5 lens. The extra reach might be great for other photographers, but given my use case I chose the wider aperture for the benefit of lower ISO in difficult shooting conditions. Given the 1” sensor, you’re unlikely to notice much of a difference in DoF regardless of which lens you choose.

Coming from my D810, chromatic aberration is an issue with this camera which Lightroom struggles to correct automatically. I often have to manually tweak the defringing settings in Lightroom as the eye dropper fails to sample what I’m seeing. The built-in lens profile does a good job of correcting distortion, however I automatically add +10 vignetting on import to Lightroom as the corners tend to come out a bit dark across all focal lengths.

In terms of autofocus, I find myself using Wide or Expand Flexible Spot modes most often depending on what I’m shooting. Quick trip out with the family? Wide more for fast focus. Shooting a blog post? Expand Flexible Spot for accuracy. I’m a proponent of focus and recompose, which I’ve accomplish by disabling AE Lock on the 1/2 shutter press. I focus on my subject with a 1/2 shutter press, recompose, and take the shot (I have AE Lock mapped to another button on the off-chance I need it). It’s EXTREMELY easy to miss focus at infinity for some reason, and I stopped using Center mode because it would often grab the foreground vs the building off in the distance I was aiming for. If you think you’ve missed focus, use the zoom toggle to quickly zoom in 100% and check critical focus. This feature is also handy if you think there might be some camera shake in your picture.

Information on the RX100VA’s lens is sparse online, but through my own testing I’ve been able to nail down the sharpest apertures and focal lengths.

One quirk of the RX100VA is it’s minimum shutter speed calculation. The old adage “1 / focal length is the minimum shutter speed to avoid camera shake induced blur” holds true, however I’ve found the minimum shutter speed calculated by Sony to be optimistic at times. Don’t try shooting one handed with the EVF as you’re bound to get some camera shake in the resultant image. You can always adjust the ISO AUTO Min. SS from Standard to Fast if you want to be safe. I first did this when I realized 1/4 of my shots were blurry from camera shake and have since improved my technique enough to revert back to Standard.

Not specifically lens related, but the RX100VA has a handy built-in flash that I’ve used a few time for pictures of the family in not-so-great lighting conditions. It works well and isn’t too harsh when set to “Fill Flash”. I’ve certainly appreciated it when there just wasn’t enough light for the ISO/Aperture combination I needed.

Ergenomics

For a compact camera, the RX100VA has some great quality of life features I’d expect coming from a DSLR. For one, the pop-up EVF is ingenious. It retracts into the camera body when not in use and allows you to get into that classic camera shooting position, which affords extra stability for longer shutter speeds. There’s also a tilting LCD (not a touch screen, which I think is a drawback given Sony’s atrocious menu structure) which makes getting low angle, high angle, or selfie style shots a breeze. I don’t love EFVs in general as someone who stares at a screen for a living and shoots lots of film, however I have nothing but praise for the Sony engineers who managed to fit one into this tiny camera!

Another great feature is that you can assign the ring around the front lens to act as a stepped zoom, offering the focal lengths of 24, 28, 35, 50, and 70mm. One of the first things I learned in photography is to treat your zoom lens as a collection of primes. I like to zoom with my feet, and the stepper zoom makes it easy to quickly select the focal length I need. There’s a menu setting which allows you to change the zoom speed from normal to fast - while you might hear the mechanical zoom with the onboard mics when recording video, you’ll appreciate the faster speed if you primarily shoot stills like me.

The one thing this camera should’ve come packaged with is the optional accessory grip. It’ll run you an extra $15 but will make this tiny camera a bit easier to hold. For a simple adhesive grip that you slap on the front of the camera, it really made a difference in handling to me.

Image Quality

In terms of image quality, this camera packs a punch with its 1” ~20 megapixel sensor and surprisingly flexible ISO range. Unlike my D810 where I use dedicated command dials to control ISO and aperture, I leave the RX100VA on Auto ISO (lower limit 125, upper limit 3200). In really dark situations I can find a nice ledge to set the camera on, adjust my settings manually, and take longer exposures with the self-timer to get a clean image. I also like that the high megapixel count leaves plenty of room to crop without sacrificing resolution. I’ve found the sensor to struggle most with highlights and the meter to tend toward overexposure. I have a permanent -1/6 exposure adjustment programmed into the camera which has mostly solved my issues. Areas around highlights (think bright sky or windows) are prone to wash out. Lightroom’s Auto White Balance function doesn’t seem to work well with this camera either. I usually adjust the tint slightly by hand or use the eye dropper to get things looking natural.

There was a STEEP learning curve in Lightroom to produce final images that hold up against my D810, but with a good amount of editing it can be done. I’ve been a Nikon shooter since my first camera, a D5500, and I’m used to the way Lightroom renders my Nikon’s .NEF RAW files. After lots of tweaking, I finally created a Lightroom import preset that I’m happy with. I’ve found the .ARW files my RX100VA produces have a slightly green tint (I’ve tried everything to fix it), need a ton more sharpening, and need a hint of clarity and dehaze to look good. You can see my default import settings below:

Develop Module

Clarity | +10

Dehaze | +8

Lens Correction

Vignetting | +10

Detail

Sharpening | +40

Radius | 1.3

Detail | 25

Masking | 15

Calibration (I used this to get rid of the terrible green cast I was seeing):

Shadows

Tint | +10

Red Primary

Hue | -10

Saturation | +5

Green Primary

Hue | +15

Saturation | -5

Blue Primary

Hue | 0

Saturation | +9

My Travel Kit

The RX100VA is a camera I aim to always have with me when traveling, and as such I have a go-bag with everything I need for a day of shooting. Here’s a list of what I carry:

Sony LCS-CSJ Carrying Case

Op-Tech USA Strap | I keep a set of clips on my RX100VA and the case itself so I always have the strap with me. The camera won’t fit in the case with a neck strap attached.

2-3x NP-BX1 Batteries | This camera absolutely eats batteries. You can expect about 220 shots per battery, in my experience. Expect less shots if you extensively use the EVF.

Sandisk Extreme Pro 64 GB SD Card | This will get you a ton of shots - 1,761 in RAW + JPG (fine) to be exact. No need for a bigger card unless you plan to shoot lots of 4k video.

Microfiber Cloth & LensPen Micro

Lens Cleaning Wipe (for LCD)

WhiBal G7 Keychain Card | Like I mentioned above, getting the white balance right can be tricky. This little card fits neatly within the carrying case and comes in handy when I want to shoot an 18% gray target in tricky lighting situations. I leave my RX100VA on Auto White Balance: White.

Tom Bihn Zipper Pouch

Sony BC-DX2 Charger + USB Wall Adapter | While you can charge batteries in the camera itself, this handy little charger comes dirt cheap in a kit from B&H. Worth it for charging batteries on the go while leaving your camera safe and sound in it’s case.

Apple Lightning to SD Card Reader | I often leave my heavy 2021 MacBook Pro at home when traveling, so this adapter allows me to browse a day’s work from my iPhone or iPad.

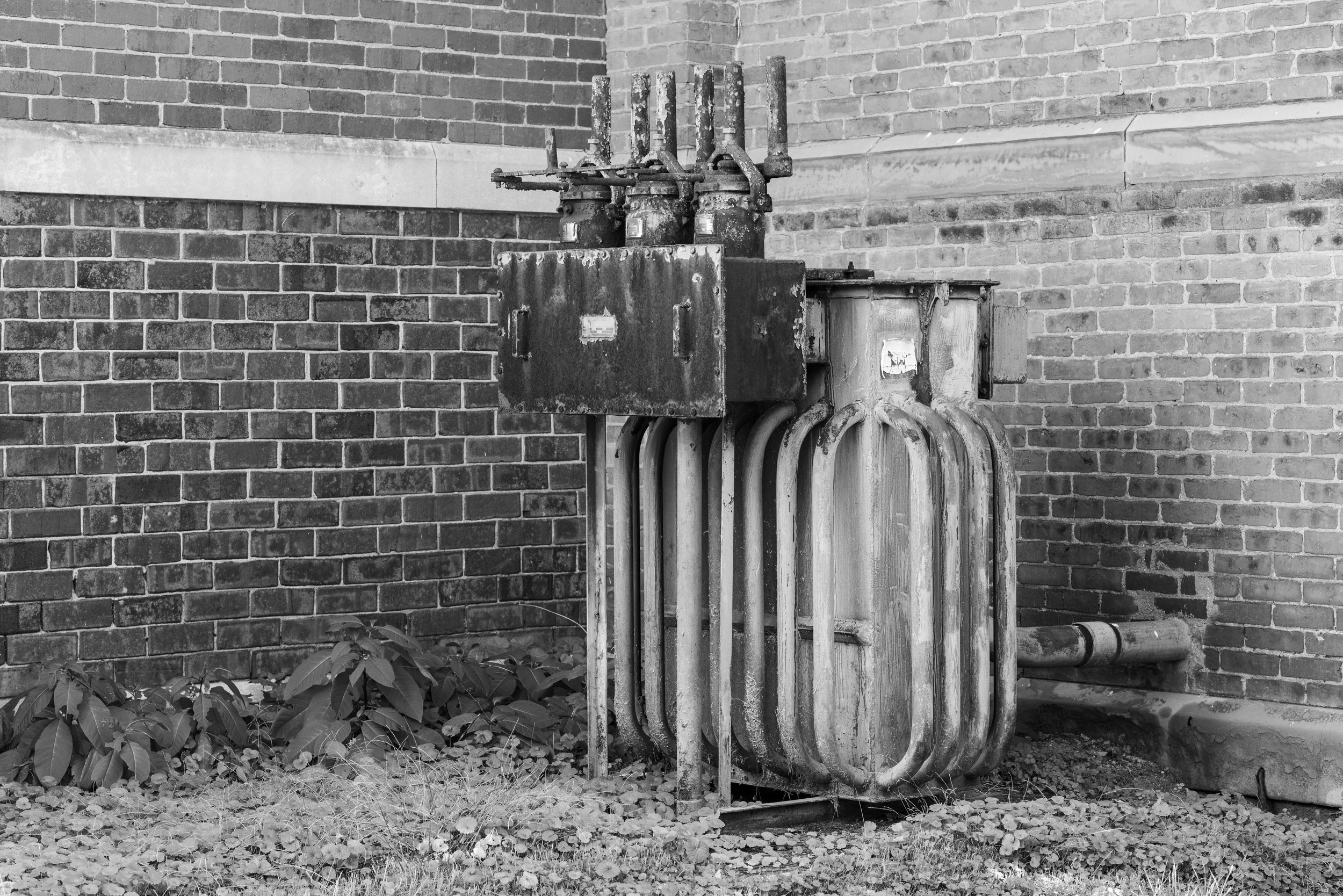

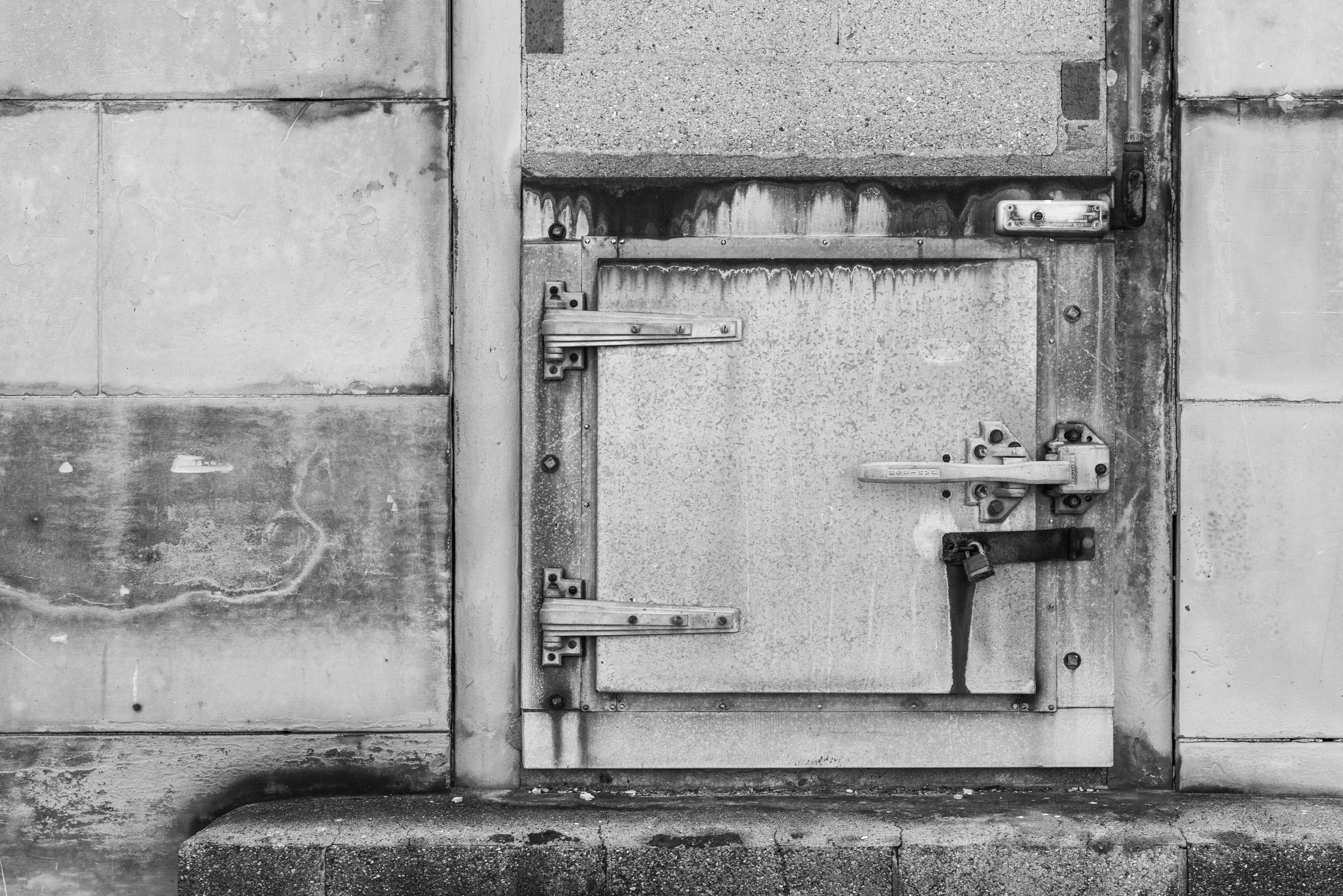

Test Shots

I purchased the RX100VA to have a camera that could easily travel with me on my trips downstate, to be used for blog posts when I didn’t have time to haul my D810 with me, and to capture more moments with my family. The RX100 series also excels at video but I haven’t had much experience with that aspect of the camera. I’ll be sure to update here if I ever dive into it. You can see some of the blog posts I’ve made which were shot on the RX100VA linked below:

The Verdict

In an age where content is increasingly being consumed on the small screen and iPhone photography prevails, I think there’s still a place for a compact camera in the photographer’s pocket. The main benefit I find with the RX100VA is it’s ergonomics which make it such an enjoyable little camera to use. While I’ve repeatedly considered fixed lens alternatives like the Sony RX1 and Fujifilm X100 series, I think the flexibility of the RX100VA’s zoom lens is too valuable to pass up. What probably matters most is I now have a high quality camera with me when I would’ve been empty handed, enabling me to shoot more blog posts, get out in the field, and live up to the tagline of my site: History | Exploration | Photography.