Fujifilm’s line of instant film, known as Instax, is all the rage these days. Introduced in 1998, Instax film stuck around while Polaroid died a slow death beginning in the early 2000s. And in an age of digital photography and camera sensors which can resolve an insane amount of detail, there’s still a certain thrill that comes along with watching a color print develop right before your eyes.

Some exciting things are happening in the world of film, from Pentax announcing the development of a new film camera to Fujifilm investing millions towards new film production at their factories outside Tokyo, Japan. Fuji even released my favorite 100 ISO black and white film, Across 100, in 120 format within recent years. Now if only they’d release it in 4x5…

Now instant film is fun and all, but the current line of Instax cameras just can’t satisfy my obsessiveness over controlling every aspect of the image-making process. Instax cameras are geared towards the casual photographer, and most models offer only the most basic exposure controls. But what if you want to push the film to the max with camera movements, varying depth of field, or off-camera flash? Clearly somebody else at Lomography had the same idea because they created this nifty attachment called the Lomograflok. If you happen to have a 4x5 camera laying around with Graflok tabs then you’re in luck!

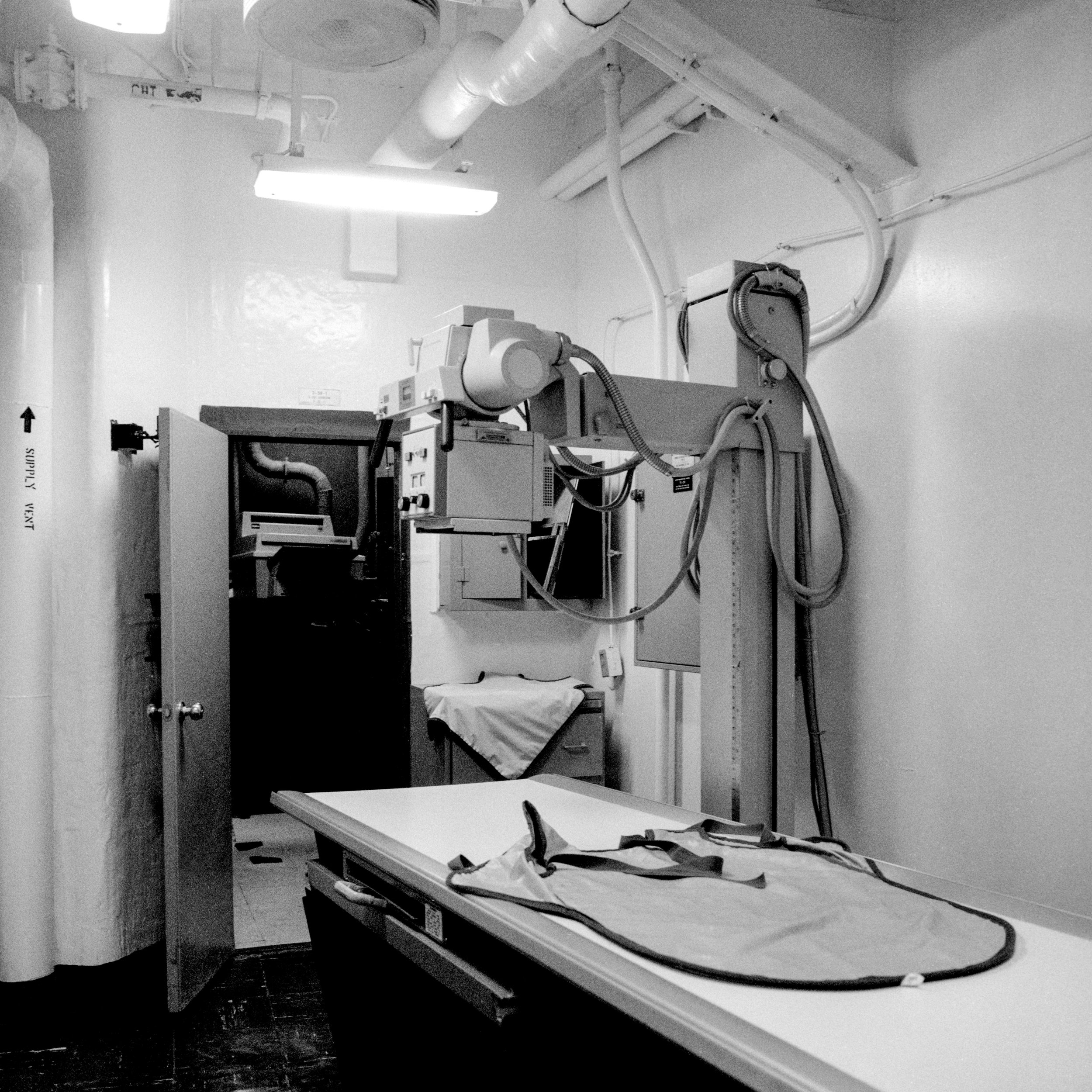

Through the magic of the Graflok attachment system, you can easily shoot Instax images using your large format camera. Simply add a pack of Instax Wide film, throw in some AA batteries, and you’re on your way to instant color prints. Just don’t forget to bring a dark cloth with you like I did… you’ll still need it!

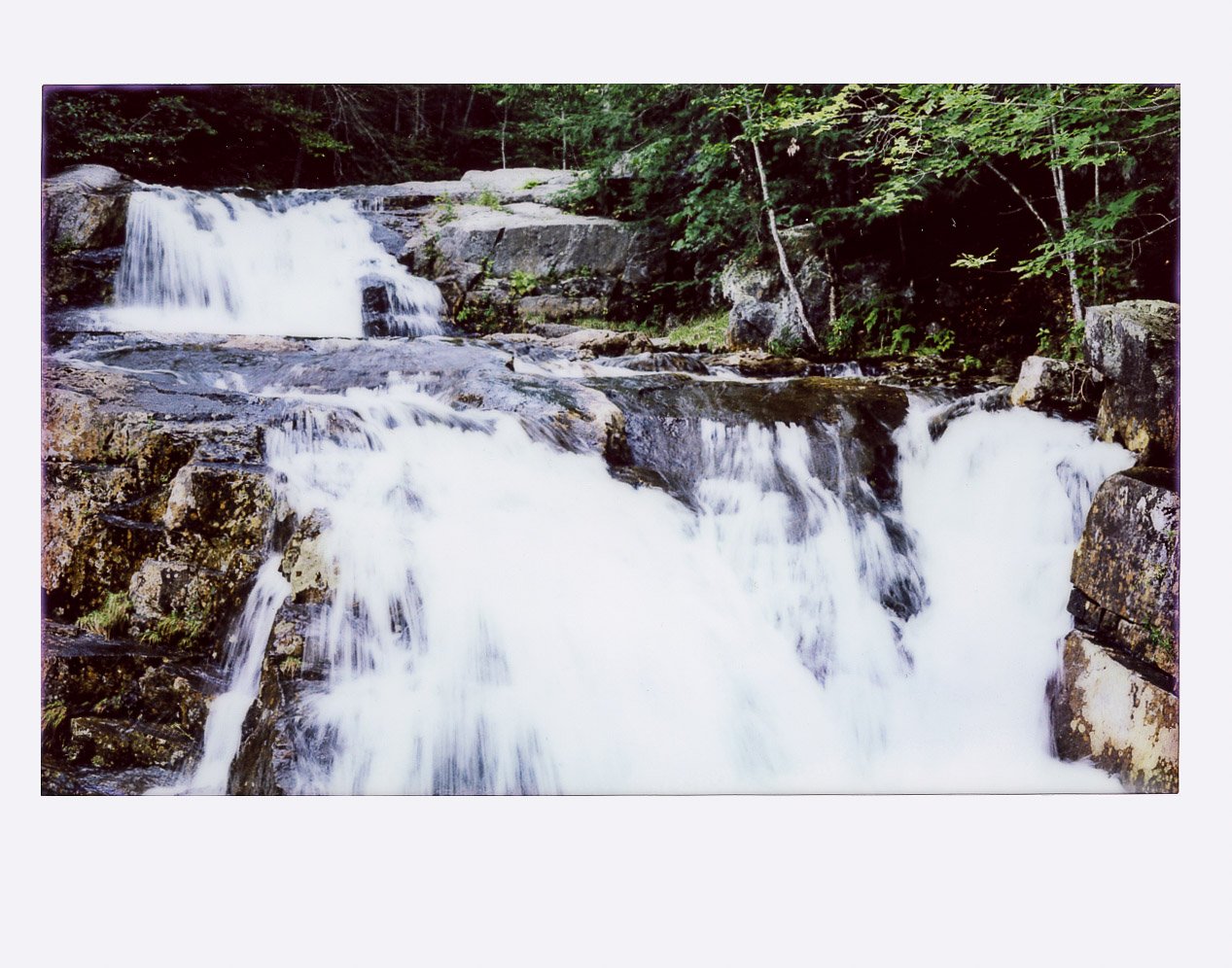

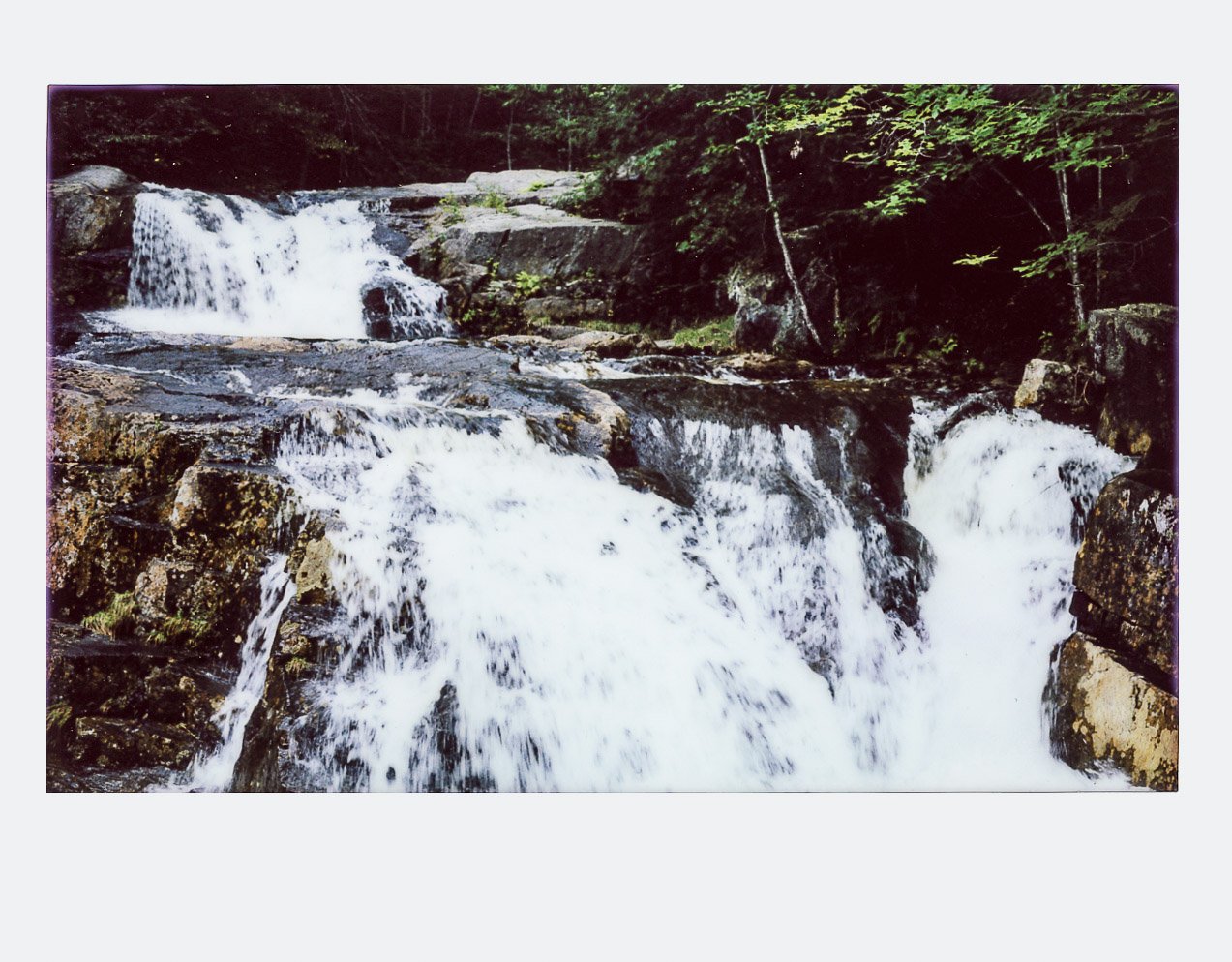

Sample Instax Images

NIkon 150mm @ f/32, 1/250 sec.

I’ll preface this review by saying that if you’re after absolute image quality, Instax will leave you disappointed. You won’t be blowing up an Instax shot to 200% in Lightroom to check for critical sharpness, and the prints are actually quite frustrating to scan/edit. Instax film resolves 10 lines/mm at best - for reference, Kodak T-Max 400 can resolve 10x the detail in B&W. Shooting Instax on 4x5 is just a fun, fast way to get a color image in the field. The images I took looked nothing like the advertising images you’ll see on Fuji’s website.

If you put technical details aside and focus on the fun then I’d say the Lomograflok back is a worthwhile purchase. Shooting Instax isn’t much more expensive than shooting 4x5 film at about $1 per exposure. As an added bonus, there’s no need to send any color film off for development if you’re like me and don’t shoot enough C41 or E6 to justify keeping color chemistry on-hand. You also avoid the tragedy of the USPS losing your exposed 4x5 Ektachrome in the mail… ask me how I know what that feels like.

The Lomograflok itself is a neat little device, and I feel the build quality matches the $175 price tag. To start making prints, you first compose your image using the ground glass and a special mask that’s provided with the Lomograflok back. The final image only takes up a portion of the 4x5 ground glass, and the mask also helps align your point of focus to the Lomograflok’s recessed film plane. Instax film comes in three sizes: Mini, Square, and Wide. The Lomograflok back uses Instax Wide film with an ISO of 800 that produces a picture of 4.3 in. × 3.4 in. in size.

Once you’ve squared away the composition and focus, you’re ready to install the Lomograflok back on the camera. Remove the ground glass and attach the Lomograflok with the locking tabs of the Graflok system, making sure the locking tabs are fully engaged. Next, open the back of the Lomograflok and pop an Instax cartridge in. Just like you would with a typical film holder, you’ll set the lens aperture/shutter speed, remove the dark slide, and make an exposure. Pressing the eject button spits out your image as small rollers in the back squeeze out development chemicals over the film. Within 90 seconds you’ll be able to see the results of your work!

Every pack of film gives you 10 exposures, which I found was just the right amount for a weekend of shooting. You’ll also need 4x AA batteries, and my Enloop rechargeables lasted me both packs of film I had on hand.

So what have I learned over my first 2 packs of Instax Wide film shot with the Lomograflok? Here’s some struggles I faced and tips I learned along the way:

Out of my first 10 shots, I had 6 successful images. I lost two by reason of over exposure, one to poor framing, and another to poor composition (completely my fault). Incident metering with my Sekonic L-508 seemed to produce more consistent results than reflective metering.

While Instax film is rated ISO 800, I recommend underexposing about 1/3 of a stop to protect highlight details. Crushed shadows look better than blown highlights with this film. It’s incredibly easy to end up with a completely white sky if you aren’t careful.

While Instax film develops in 90 seconds, I found it takes another few minutes for blacks to fully develop. Contrast vastly improves with time.

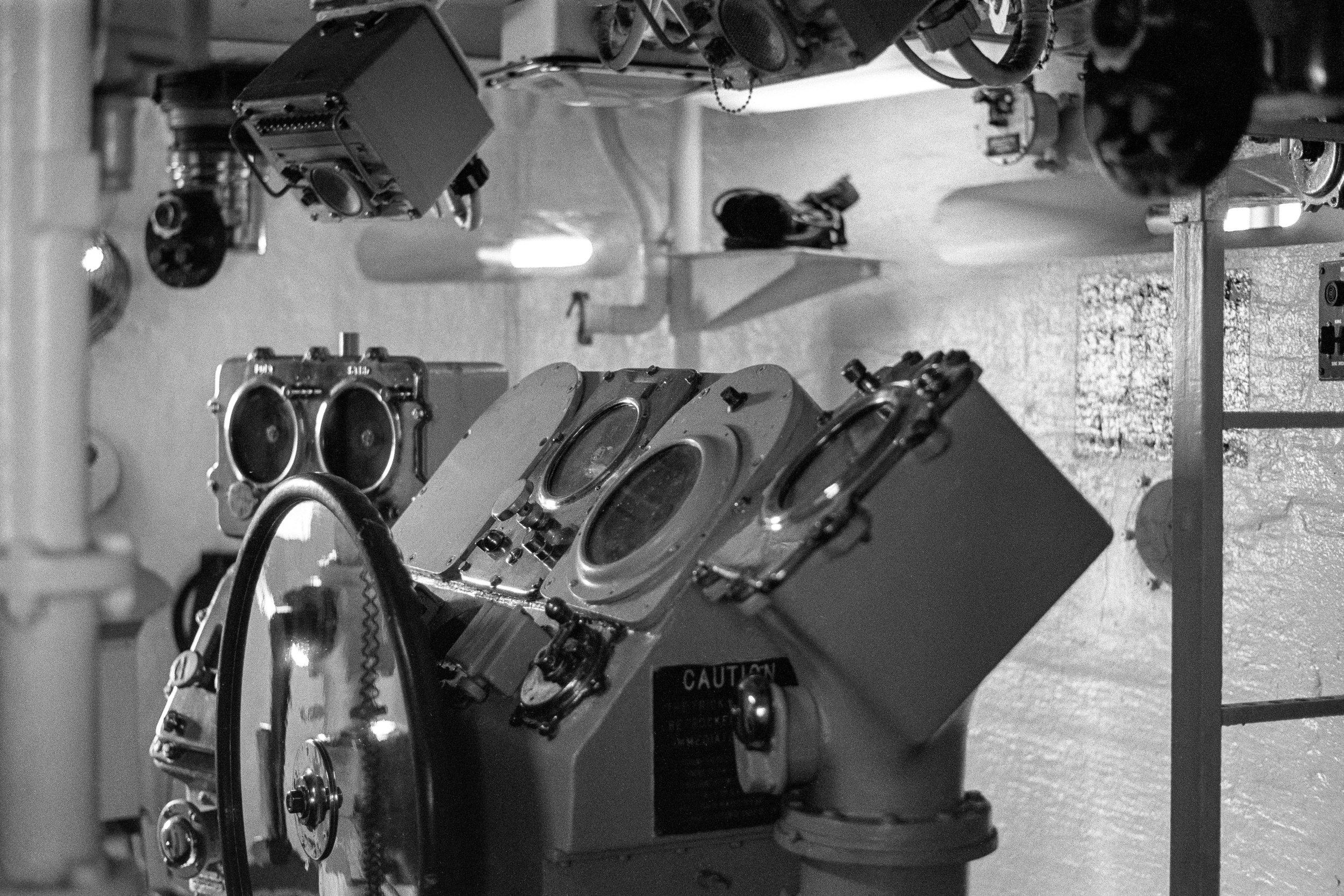

The high ISO of Instax film poses significant challenges with the comparatively slow shutter speeds that large format Copal shutters are capable of. Copal 0 shutters are capable of 1/500 sec. speeds while Copal 1s max out at 1/125 sec. The image of a sign post you see above was actually overexposed at 1/125 sec. and f/64, but that’s the best I could do without an ND filter. My Nikon 270mm f/5.6 just ran out of shutter speed and aperture to cut out the bright sunlight. Luckily the film is so low-resolution that diffraction really isn’t noticeable.

Be extremely careful with close subjects and leave a little room for unintentional cropping around your subject. The shot I lost to poor framing which looked right on the ground glass but was cropped tighter than intended.

Hopefully some of the information above and sample images here have helped you decide whether the Lomograflok is for you. The limitation of ISO 800 speed film, narrow dynamic range, and relatively slow shutter speeds inherent to large format is really the only thing that makes me second-guess the Lomograflok. Looking past the technical aspect, I think the fun of shooting Instax outweighs the technical difficulties of adapting it to a format for which it was never intended.

NIkon 270mm @ f/36, 1/125 sec.